by Alan Briskin | Collective Folly, Conscious Capitalism, Photography, Politics

A serial journal of cogent reflections and irreverent insights on the social effects of capitalism and the roots of partisan politics. Pairing prose with HDR photography and “flash points” drawn from current and historical perspectives, the author seeks to recover lost wisdom and courageous action beyond the shouting and noise of today’s headlines.

Chapter Ten

Corporate Persons

What Does Not Serve Me Shall Not Be My Concern

Time Range: 1985-Present

Who even knew that corporations had legal rights as if they were actual persons? In a strange twist of legal gymnastics, the originating idea of a corporation being birthed and legitimized by a government grant had been transformed into a corporate body beholden to no one but its owners.

Economic self-interest was the law of the land, and the corporate persons cultivated in such an environment could be as sweet as your dear auntie or as self-serving and weird as the guy down the block wearing just a raincoat. However, both would be legally obligated to prioritize their shareholder economic interests over other concerns such as the corporation’s effect on human beings or the earth’s resources. Economists even have language for this. Externality is the effect on others, positive or negative, by corporate action that is not calculated into the cost of the goods or services.

“An externality,” wrote the economist Milton Friedman, “is the effect of a transaction … on a third party who has not consented to or played any role in the carrying out of that transaction.” He offers a relatively benign example of a man who must clean his shirt more often due to smoke emissions from a local power plant. He tends to minimize the effects by calling them “neighborhood effects” or “spillovers.” In a free market, positive and negative externalities theoretically cancel each other out or are eventually internalized by the corporation. However, a less cheerful view might look something like this: persons who dissociate their actions from their effects on others are called sociopaths.

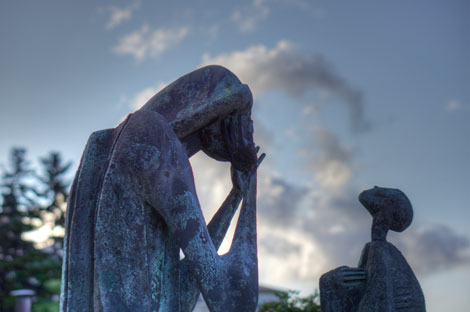

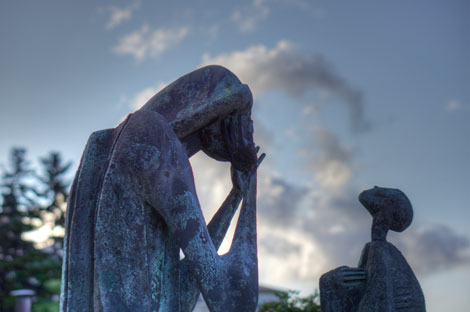

HDR (High Dynamic Range) Photography by Alan Briskin: multiple shots at different exposures are combined into one image in order to show “more of what’s there”.

Sociopathic corporate persons would not hesitate to market cigarettes or foods high in toxic chemicals, trans fats, sugar, and salt. They would simply point to positive externalities such as jobs being created or the social benefits of smoking and snack foods. They would feel unjustly picked on, pointing out that government intervention is a slippery slope leading to arbitrary interventions. What next, they would ask, bread with too many carbohydrates? The same logic would be offered as a defense of corporations generating air and water pollution, battling safety regulations, depleting fish stocks, wiping out forests, or underfunding pension funds. Why pick on us?

Marx’s warning that capitalism would spawn a consciousness of immediate economic self-interest takes on darker shading when extrapolated through corporate externalities influencing climate change, epidemic rates of diabetes and obesity, international instability, and increasing numbers of retirees without adequate access to basic needs of food, housing, and health care. The point is not that these things are easily fixed or that government will always get the balancing act right, but that corporate sociopaths, with society’s legal approval, have a built-in incentive to muddy the water.

FLASH POINTS

FLASH POINTS

Big

Tobacco says that smoking is about freedom and choices. But a battalion of

experts at Emory is showing that better choices can be made—and that not much

about tobacco is free…

“Industries like gambling, alcohol, and tobacco are ‘societal cancers,’ says [Ray] Gangarosa, that cause ‘exceptional social harm, including death, disability, addiction, and secondhand injury, on the scale of a commercial holocaust . . . (and have) escaped society’s usual controls by shifting blame for harmful commerce to their consumers, and then shifting associated downstream costs onto society. We must hold these harmful industries accountable for their costs.’

Gangarosa, who is working toward a PhD in epidemiology at RSPH [Rollins School of Public Health], was disappointed in the Master Settlement Agreement, in which he feels ‘some terrible compromises were made.’ But he acknowledges the complexity of the issue. ‘The tobacco industry doesn’t make enough money to pay for the social harm that they do. We would bankrupt them,’ says Gangarosa. ‘But if we don’t ask them to pay the social cost, then they are effectively being subsidized.’”

~ Public Health, Spring 2002

“After getting called out by an environmental group, General Motors has pulled support from the Heartland Institute, a Chicago-based nonprofit well-known for attacking the science behind global warming and climate change.

The automaker told the Heartland Institute last week that it won’t be making further donations, spokesman Greg Martin said. At a speech earlier this month, GM CEO Dan Akerson said his company is running its business under the assumption that climate change is real.”

~ Huffington Post, March 30, 2012

“Corporations Are Not People”

“Can grassroots victory in Green Mountain state spark national movement?

“With some results still yet to come in, reports confirm that at least 55 towns in Vermont approved municipal resolutions calling for an end to big money’s dominance in US politics and calling for a Constitutional amendment to reverse the Supreme Court’s ‘Citizens United’ decision that has opened the floodgates for secretive, unlimited campaign spending in US elections.

“The initiatives called on the Vermont Legislature and the state’s congressional delegation to support a constitutional amendment that clarifies that ‘money is not speech and corporations are not people.’”

~ Common Dreams, March 7, 2012

Next Week:

Chapter Eleven: Booms and Busts

The bull market of the 1980s saw greater numbers of people investing and realizing larger returns. A whole new financial investing industry was growing up alongside corporate growth. Workers were working longer hours and taking on second jobs, but day traders could get rich in an instant. As we headed into the ’90s, the political focus was on the economy, stupid. A new president argued that government could smooth out the economy’s rough edges, and by playing by the rules and working hard, we might finally see an end to capitalism’s wild gyrations.

by Alan Briskin | Business, Conscious Capitalism, Consciousness, Leadership

A serial journal of cogent reflections and irreverent insights on the social effects of capitalism and the roots of partisan politics. Pairing prose with HDR photography and “flash points” drawn from current and historical perspectives, the author seeks to recover lost wisdom and courageous action beyond the shouting and noise of today’s headlines.

Chapter Nine

Wages Decline, Credit Expands, Rapidly

Time Range: 1978-1985

What I did not know, setting my sights on creativity and meaning, was that the economic rocket ship we were on was about to sputter and go sideways. For 150 years, capitalism in the United States had functioned, despite its busts and booms, to move in an upward spiral. Working people, on average, saw their real wages rising decade after decade.

Until the 1970s, every generation had a reasonable chance to expect a better life than the previous one. Imagine if my father had not believed that. If he had believed that his sacrifices would make little positive difference for his children’s circumstances. Yes, he was disappointed in me and likely wondered if my crazy talk would ever lead anywhere, but I was in college. I would have a degree that was never an option for him. Anti-Semitism was on the decline. He had no reason to fear that roads would be blocked in front of me. And they were not, but wages for the average worker hit a wall.

From 1978 to 2011, real wages after adjusting for inflation went flat, nada, nothing. I’ll say it again. As best as we know from our economic models, there have been no wage increases for the average worker since the year I finished working at St. Johnsbury prison in 1978. This means that many of the inmates who found jobs in lumber mills, retail services, maintenance, and construction would be earning exactly the same amount today, once adjusted for inflation, as when they began. Or they might be unemployed. How did this come about?

Dr. Richard Wolf is an economist with an impeccable professional pedigree. He received his undergraduate degree at Harvard, his master’s at Stanford, and his doctorate at Yale. He was educated at institutions with a reverence for capitalism but supplemented his studies with a curiosity about its critics, most notably Karl Marx. He argues that beginning in the 1970s, there were at least four trends that help us put today’s circumstances in perspective.

HDR (High Dynamic Range) Photography by Alan Briskin: multiple shots at different exposures are combined into one image in order to show “more of what’s there”.

The first was the introduction of new technology, accelerating the use of computers to replace labor. Imagine, for example, the use of scanning devices to replace people physically counting business inventories. Human beings count slowly and get distracted. Forget jobs that are repetitive and can be automated. Gone.

Second was the increasing use of offshore factories for manufacturing. Recall that surplus value is enhanced when the cost of labor decreases. Finding workers on other continents who could be paid less was the perfect marriage of increasing profit while simultaneously creating new markets.

Third was downward pressure on wages as an increasing number of women and immigrants entered the workforce. This was the period when corporations began to deal with the visible reality of diversity, but the economic effect of a greater labor supply was far less visible or obvious. Women were consistently paid less than their male counterparts, and the greater overall labor supply meant more competition for jobs, thus creating a labor market in which supply outstripped demand.

The fourth trend was a response to the first three, increased use of personal debt. As the earning power of workers was eroding, the rapid rise of credit cards began to supplement income, but at a huge cost. Will Rogers’s famous aphorism that when you find yourself in a hole, stop digging, became instead a search for bigger shovels. And there was no bigger shovel than credit cards and eventually mortgage debt. All these developments were slow moving and never in a straight line, but we can now see where they were leading.

Other social and economic forces were operating as well. In roughly the same 30-year period when workers’ wages were slowing down to a crawl, Fortune 500 companies saw corporate profit increasing as they grew in size and complexity. Amid this growth, fascination with the organizational leader (CEO) became quasi-cultish, symbolized by life-sized cutouts of Chrysler’s CEO, Lee Iacocca, filling bookstore windows. His autobiography was the best-selling hardcover nonfiction book in both 1984 and 1985. And just two years earlier, the birth of popular management books began with the hugely successful In Search of Excellence, attributing success to management savvy.

The success part turned out to be illusory, but the fascination with heroic leadership and management techniques became a major industry. Meanwhile, no one paid attention to the calculus of surplus value, how limiting wages was a driver of capital profits. In academia and professional consulting, we may have become more conscious of organizations as systems and the need for strategy, discipline, and leadership, but as citizens, we for the most part did not question the economic institution we operated within. We were, to put it simply, unconscious of capitalism and its myriad influences.

FLASH POINT

FLASH POINT

San Francisco, 1984

In a friend’s San Francisco apartment, I dictated my doctoral dissertation from handwritten notes to a typist working with one of the first home computers. For someone who had never mastered the typewriter and whose handwriting was virtually illegible, this was a technological event with great personal meaning. Advances in technology literally gave me an opportunity to pursue my life’s work.

The subject of my dissertation, however, was somewhat off the beaten trail of society’s progress. I was researching the parallel historical conditions of social institutions such as prisons, mental institutions, public schools, and workplaces. My thesis was that surveillance and control had become dominant characteristics of these institutions, resulting in the institutionalization of the soul. We were losing a fundamental relationship with both nature and our own inner world. We were losing a spiritual connection to the transcendent, a perspective larger than just our own self-interest.

What I had not considered was another kind of person who was gaining greater and greater freedoms. This was the corporate person. I don’t mean the organizational man of the ’50s and ’60s. I’m talking about a corporate entity with the legal rights of a person and whose sole legal concern was self-interest.

Next Week:

Chapter Ten: Corporate Persons: What Does Not Serve Me Shall Not Be My Concern

Who even knew that corporations had legal rights as if they were actual persons? In a strange twist of legal gymnastics, the originating idea of a corporation being birthed and legitimized by a government grant had been transformed into a corporate body beholden to no one but its owners.

Economic self-interest was the law of the land, and the corporate persons cultivated in such an environment could be as sweet as your dear auntie or as self-serving and weird as the guy down the block wearing just a raincoat.

by Alan Briskin | Conscious Capitalism, Consciousness, Leadership

A serial journal of cogent reflections and irreverent insights on the social effects of capitalism and the roots of partisan politics. Pairing prose with HDR photography and “flash points” drawn from current and historical perspectives, the author seeks to recover lost wisdom and courageous action beyond the shouting and noise of today’s headlines.

Chapter Eight

Planetary Consciousness Arises, Cautiously

FLASH POINT

FLASH POINT

Himalayas, 1964

“Slowly and painfully, we are seeing worldwide acceptance of the fact that the wealthier and more technologically advanced countries have a responsibility to help underdeveloped ones. Not only through a sense of charity, but also because only in this way can we ever hope to see any permanent peace and security for ourselves.”

~ Sir Edmund Hillary, Schoolhouse in the Clouds

World Population, 1967

“[H]istorians have estimated that the world’s population at the beginning of the Christian era was 250 million. By the middle of the seventeenth century it had doubled, rising to about 500 million. By the middle of the nineteenth it had doubled again and reached the first billion mark.… By 1965, it was well over three billion, and the doubling period had shrunk from 1,500 years to about 35 years …

“Returning to the planet as a whole, the prospect is: 7 billion people in 2000; 14 billion in 2035; 25 billion a hundred years from now. ‘But,’ as a sober Ford Foundation report says, ‘long before then, in the face of such population pressure, it is inevitable that the Four Horsemen will take over.’”

— Arthur Koestler, The Ghost in the Machine

United Nations, 1969

United Nations, 1969

I do not wish to seem overdramatic, but I can only conclude from the information that is available to me as secretary-general that the members of the United Nations have perhaps ten years left in which to subordinate their ancient quarrels and launch a global partnership to curb the arms race, to improve the human environment, to defuse the population explosion, and to supply the required momentum to development efforts. If such a global partnership is not forged within the next decade, then I very much fear that the problems I have mentioned will have reached such staggering proportions that they will be beyond our capacity to control.

— U Thant, Secretary-General, United Nations

HDR (High Dynamic Range) Photography by Alan Briskin: multiple shots at different exposures are combined into one image in order to show “more of what’s there”.

New York City, 1973

In the early 1970s, I worked summers for my father delivering packages and assembling hand machines that stapled nailheads and rhinestones into fabric. His shop was almost exactly two miles from the Triangle Shirtwaist Factory on 23–29 Washington Place, which burned down in 1911. It was hot and muggy in his shop, and I didn’t enjoy working there, but it was nothing like the sweatshops that had existed over a half-century earlier. One reason for this was unions.

Marx was correct in predicting, counter to the sentiment of his time, that workers would not simply have more children, diluting their bargaining power, but would become ever more skillful in negotiating their immediate and mostly economic self-interest. For Marx, however, it would be this very advance that would trigger the system’s instability, as the workers’ demands would threaten profit and control. Owners would reject their workers’ ever-increasing demands, and workers would seek to strike back. Marx was quite certain that both sides would remain unconscious of their predicament. They would battle ceaselessly with each other until social unrest upended the whole system. How different circumstances were for me.

I recall one evening riding home with my father on a bus that took us from Manhattan to Queens. He wondered if I would be interested in taking over the business one day. It was an awkward moment between us, and I sat in silence looking out the window. “I don’t think so,” I mumbled. He didn’t respond, and we sat together in silence the rest of the way.

For me, taking over the business would have been abandoning myself. I would have preferred stapling nailheads through my hand. I was in college and passionate about finding alternatives to what I believed were soul-crushing institutional forces beginning in public schools and continuing through college, professional education, and most definitely the workplace.

My plan was to chart a new path, although how I might do that was unknown to me. I shared, with many others, a belief that economic survival was no longer the key determinant of career choices. Survival was at the bottom of a hierarchy of needs that included meaning, creativity, and human development. The work of the future involved social change, greater personal and interpersonal depth, and healing our planet earth. The stars in the sky proclaimed that this was the Age of Aquarius—or at least the stars on Broadway shouted it out loud, which was good enough for me.

Next Week: Wages Decline, Credit Expands, Rapidly

What I did not know, setting my sights on creativity and meaning, was that the economic rocket ship we were on was about to sputter and go sideways. For 150 years, capitalism in the United States had functioned, despite its busts and booms, to move in an upward spiral. Working people, on average, saw their real wages rising decade after decade. Until the 1970s, every generation had a reasonable chance to expect a better life than the previous one.

From 1978 to 2011, real wages after adjusting for inflation went flat, nada, nothing. I’ll say it again…

by Alan Briskin | Collective Folly, Conscious Capitalism, Politics

A serial journal of cogent reflections and irreverent insights on the social effects of capitalism and the roots of partisan politics. Pairing prose with HDR photography and “flash points” drawn from current and historical perspectives, the author seeks to recover lost wisdom and courageous action beyond the shouting and noise of today’s headlines.

Chapter Seven, Part Two

How Wealth Became Concentrated and the Poor Were to Blame: What Should Be Done with the Poor?

For the record, Harrington tried to address the dilemma of what constituted poverty, but his efforts backfired. He acknowledged that poverty was a social and historical construct, different in different time periods and cultures. He believed, like Roosevelt, that those without minimal levels of health, housing, food, and education were poor — especially when those same resources were available to the larger population. It is with this definition that he arrived at the 40–50 million figure of poverty in 1962.

Harrington came to believe that poverty was a function of reinforcing social elements that shaped an individual’s outlook. The outlook of the poor was different from the outlook of those who, like my parents, had hope for a better future. In that context, he believed that government had a critical role to play, but the real backdrop was the inadequate functioning of our economic and social institutions. Poverty resided in diverse physical locations and with different populations, but all faced similar obstacles. What were they?

HDR (High Dynamic Range) Photography by Alan Briskin: multiple shots at different exposures are combined into one image in order to show “more of what’s there”.

FLASH POINT

FLASH POINT

Mitt Romney Criticized By Franciscan Friars For Comments On The Poor

Alex Becker

Huffington Post

Posted: 08/09/2012 2:36 pm Updated: 08/09/2012 3:55 pm

WASHINGTON- The Franciscan Action Network (FAN), a Catholic faith-based advocacy and civic engagement organization, is strongly criticizing Mitt Romney’s recent ads and rhetoric regarding welfare programs and welfare recipients, urging him to spend some time in low-income communities.

“Our Christian tradition teaches that we are to treat the poor with dignity and to prioritize the poor in our policies as a society,” the organization said in a press release on Thursday. “At a time when millions are struggling financially, it is degrading to talk about the ‘dependency’ of people hurting in this economy, as Gov. Romney did recently.”

Rhett Engelking, a secular Franciscan in Milwaukee and member of FAN, has even personally invited Romney to visit with the low-income people he assists. “Political leaders would not talk about the poor in demeaning ways or cut job training programs if they spent more time with the people they are affecting with their policies,” he said.

While faith-based anti-poverty and charity organizations have often criticized candidates and lawmakers for a perceived unwillingness to highlight and tackle issues affecting the very poor, FAN claims Romney’s rhetoric goes a step further, unfairly using welfare recipients as political props.

He understood something that has only recently been supported statistically by studying geographic zip codes. Harrington argued that poverty was a toxic mix of factors that included poor health, minimal access to health care, high-crime neighborhoods, hostile police presence, failing schools, generational cycles of unemployment, low income, family instability, and inadequate diets. Overcoming any one of these factors was possible, but together they represented a vicious cycle of cumulative obstacles whose aggregate outcome was failure. For example, I have estimated that there are zip codes in my hometown of Oakland, California, in which the chances of an eighth grader eventually graduating from a four-year college are less than 6%.

A few miles away in another zip code, on the border of Oakland, the figure is closer to 90% graduation with 98% planning to attend some form of college. Naturally, the attitudes and resources of the group in which 98% aspire to college will be different from those with little evidence that they will succeed. It was in this context that Harrington attempted to address a “culture of poverty,” and the term stuck in the worst possible way.

What Harrington was hoping to communicate was the hellish interlocking forces that resulted in a systematic repudiation of individuals and the groups they came from. He added that it was not uncommon to find an attitude of futility and lack of self-worth within these settings — but he stressed that these attitudes were the symptoms, not the disease. For Harrington, the absence of what he called positive aspirational qualities was the psychological demarcation separating this new form of poverty from others, enclaves so beaten down that the individual response was passivity, self-destructive behavior, and outbursts of violence. He believed that somehow if the larger society became conscious of such a destructive spiral, they would be inspired to change it.

Looking back with hindsight, we might wonder what the hell he was thinking. Instead of altruistic regard, a backlash against the symptoms of poverty became the rallying cry for both the left and the right. The left wanted to create legislative policies and fund government programs to fix the problem; the right vilified the subjects of Harrington’s findings – the poor and marginal – as failing due to their own poor attitude and dismal culture.

Harrington’s analysis, viewed as initially catalyzing John Kennedy’s interest in the subject of poverty and later Lyndon Johnson’s war on poverty, inadvertently provided fodder for the belief that poverty was simply other. The poor were subject to character flaws of epic dimensions. These included lack of impulse control, limited sense of self, manipulativeness, unwillingness to contribute to society, and being destitute by nature if not by choice. Daniel Moynihan, a drinking buddy of Harrington’s at the White Horse Tavern in Greenwich Village and former assistant secretary of labor under both Kennedy and Johnson, compounded the problem with a report a few years later focusing on the inner city titled The Negro Family: The Case for National Action.

Now poverty would be construed as other and black, though some might question that as redundant. What is unquestioned is that the same forces that polarized during Roosevelt’s time in office now found a new subject to disagree about with each other. What Harrington tried to portray as a byproduct of failing economic and social institutions cutting across age, race, and geographic region instead became the stigmatization, if not demonization, of the poor. The culture of poverty was for many the confirmation of an existing belief. The poor were to blame for having too many children, fostering negative attitudes, lacking personal responsibility, and demonstrating an absence of respect for law and order. The poor would drag us all down if we let them.

A decade or so later, Ronald Regan would campaign against welfare queens driving Cadillacs and taking money out of our collective pockets with their welfare checks. His message was that government should not aid and abet personal misconduct. Years later, Bill Clinton would negotiate new welfare reform legislation that mandated “chastity training” for poor single mothers. As Barbara Ehrenreich pointed out in an article on the 50th anniversary of The Other America’s publication, the language of a “culture of poverty” began as a jolt of social consciousness but devolved into the cornerstone of conservative ideology. The assault from the right was that poverty was caused “not by low wages or a lack of jobs, but by bad attitudes and faulty lifestyles.”

Meanwhile, the ghost of Karl Marx snickers on a stool at the Red Lion Pub. Ehrenreich, who knew Harrington, noted the subterranean forces that may have driven Harrington to use the “culture of poverty” as an explanatory principle. “Maurice Isserman, Harrington’s biographer, told me,” she wrote, “that he’d probably latched onto it in the first place only because ‘he didn’t want to come off in the book sounding like a stereotypical Marxist agitator stuck-in-the-thirties.’” Harrington, a socialist, probably didn’t want to be dismissed for evoking the one who could not be named.

In many respects, Harrington succeeded by not being identified with Marx. However, by avoiding one pitfall, he fell into another. By offering up the idea of culture as a way to understand what was happening in America, he provided an escape valve for both sides of the debate. One side viewed the poor as evidence of an unfulfilled contract within an affluent society needing remedy; the other viewed them as a danger to society. Neither really wanted to talk about the distribution of wealth or the structural basis of social inequality. Icebergs will melt and buildings will fall before we get to that one.

Next Week:

Chapter Eight: Planetary Consciousness Arises, Cautiously

by Alan Briskin | Community, Conscious Capitalism, Photography, Politics

A serial journal of cogent reflections and irreverent insights on the social effects of capitalism and the roots of partisan politics. Pairing prose with HDR photography and “flash points” drawn from current and historical perspectives, the author seeks to recover lost wisdom and courageous action beyond the shouting and noise of today’s headlines.

Chapter Seven, Part One

How Wealth Became Concentrated and the Poor Were to Blame: “Paupers are Everywhere”

1962

“Paupers are everywhere.”

~ Complaint heard from Queen Elizabeth, late 16th century, after returning from travels in the English countryside.

Michael Harrington, political activist, socialist, and professor of political science at Queens College, was no Queen Elizabeth, but his research on poverty came to the same conclusion. As he wrote in his book The Other America, he was horrified to find that 40 to 50 million Americans lived in poverty, a fifth to a quarter of the entire US population in 1962. Where were they hiding?

He believed that a subtle shift had taken place in the psychology and culture of poverty. Whereas the tenements of the early 20th century were seething with a mixture of races and immigrants, there was enough diversity of intelligence, backgrounds, and aspirations to create a modicum of hope and vitality. There was poverty, disease, and poor housing in the past, but they were circumstantial obstacles to be overcome in a country that could provide social mobility and the promise of riches. Something about the very nature of poverty had changed from these historical antecedents.

My father and mother were never rich, but through hard work and frugality they found a way to make a living and see that their children might have more education than they did. There was hope for a better future. In the ’30s, when my parents were teenagers, the context for poverty was the Depression, and it gave them a collective sense of shared hardship and sacrifice. Poverty was a marker not so much of the person as of the times, a condition of society. The poor, which included tens of millions on low wages, had more of a voice politically and were not necessarily stigmatized by their circumstances. The 1930s were also a turning point for unions, which were able to flex their collective muscle and found themselves, just as Marx predicted, able to aggressively pursue their members’ own economic self-interest relative to wages and work rules.

HDR (High Dynamic Range) Photography by Alan Briskin: multiple shots at different exposures are combined into one image in order to show “more of what’s there”.

In the late 1930s and early ’40s, the world itself was at risk. The United States went from an economic depression into a fight with an enemy believed to be the incarnation of evil. These were tough times, and the sheer exuberance of victory over evil by the mid-’40s made it easier to believe that the forces of poverty were lessening as well. In the late ’50s and early ’60s, when my parents were finally finding success and Harrington did his research, there may have been a willingness to overlook poverty as a still important aspect of the social fabric requiring attention.

Poverty, as Harrington saw it, had now matured into something separate, multigenerational, and psychological. Separate in the sense that there were whole towns, cities, or parts of cities throughout the United States that were stuck in a downward spiral. Economic and social vitality was in the business hubs of cities, in suburbs where the affluent raised their children, and along geographic corridors, not in rural areas or urban centers, where poverty was concentrated.

Small towns were adversely affected by the greater dependence on skilled labor and technology. Smaller farms were being marginalized by greater mechanization and corporatization. Minorities increasingly congregated within inner cities, which were referred to as slums and characterized by a pervasive attitude of futility. Those who could exit such places did, and the remaining were hemmed in by tight social beliefs and attitudes. The more rural or isolated an area, the more cut off from diverse lifestyles and perspectives, the more insulated and rigid became the social milieu, and the more hostile and unforgiving was its view of others.

No longer was poverty simply across the tracks; it was a contagious mindset of scarcity, fear, and resentments. It was passed down generation after generation and socially reinforced by members of its own community. Poverty and economic hardship manifested psychologically through symptoms of anger, cynicism, and intolerance. The swelling anger that Marx predicted was not crystallized between workers and owners of capital. No, it was fragmented across race, religious, geographical, and educational divisions.

Where were the poor? In the ’60s, the poor were increasingly becoming invisible — the aged tucked away in old-age homes, poor children in failing schools, minorities in slums, rural poor in the countryside just a stone’s throw away from tourist travel. A decade later, when I worked at a state prison located in St. Johnsbury, Vermont, my job was to find local employment for inmates finishing their sentences. My territory was called the Northeast Kingdom, an area as poor as Appalachia. A tourist would never have known this from driving through the area, however — a year-round recreation destination for skiing, fall foliage, and maple syrup. How sweet it might have looked to a person just passing through.

Who were the poor? If you measured the poor by material possessions such as a television set, a refrigerator, or even a decent pair of sneakers, nearly everyone was well off. If you measured only by income, you included many still starting out toward success. If you measured by psychological factors, you risked subjective prejudice. The very idea of poverty was becoming porous, fluid, and ambiguous. Poverty was not only physically becoming separate from society; it was also psychologically separating itself from social awareness, as something to be avoided. Poverty was no longer circumstantial, as it had been for my parents, or temporary until one found productive outlets; it was an all-encompassing and pitiful predicament to be in. Harrington believed, however, that if we looked at poverty with an open heart and mind, social conscience would well up in our breast. Over a million copies of his book were purchased, a surprising number to be sure, and suggesting that something unsettled was still nagging in the American psyche.

Next Week: Chapter Seven, Part Two: What Should Be Done with the Poor?

Harrington understood something that has only recently been supported statistically by studying geographic zip codes. Harrington argued that poverty was a toxic mix of factors that included poor health, minimal access to health care, high-crime neighborhoods, hostile police presence, failing schools, generational cycles of unemployment, low income, family instability, and inadequate diet. Overcoming any one of these factors was possible, but together they represented a vicious cycle of cumulative obstacles whose aggregate outcome was failure. For example, I have estimated that there are zip codes in my hometown of Oakland, California, in which the chances of an eighth grader eventually graduating from a four-year college are less than 6%.

FLASH POINTS

FLASH POINTS