by Alan Briskin | Empathy

These past few weeks, I have been aware of the practice of deep listening. When does it happen spontaneously or as an outcome of simply being present?

At Trader Joe’s, the clerk was packing my groceries and asked “Did you find everything you need, grocery wise.” I said “I noticed you asked ‘grocery wise.’”

He looked up at me and smiled. “You never know what people might say.” “I guess that’s true, I say.”

He stated to talk but unfortunately got a catch in his throat and started coughing. “Do you need some water,” I asked. “No, no, I’m fine” and I could sense how excited he was to tell me something.

He continues with this story. “The second day I was working here, I was putting groceries away in the customer’s bag and said “Did you find everything you need?” I wasn’t really looking at the person and I hear “I don’t think that is a question you should ask me.”

“So I look up – and it’s my ex-wife.”

We talked some more and there was this wonderful little moment of how crazy, silly, strange, and unexpected life can be.

To see my updated distillation of the six stances that support conditions for creating collective wisdom, see Five Essential Practices.

by Alan Briskin | Collective Wisdom, Consciousness, Fields

Teilhard de Chardin’s Noosphere: A Field of Consciousness Surrounding Us

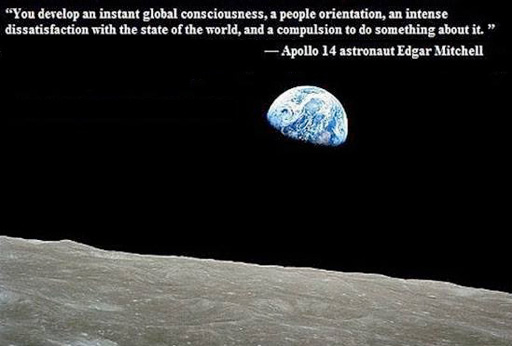

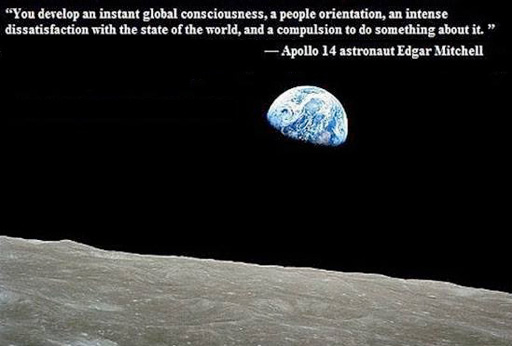

The genesis of a great idea can lie dormant for a very long time before ascending into consciousness. For the philosopher, scientist, and theologian Pierre Teilhard de Chardin, it was germinated in the mud of Verdun, France, where, as a stretcher bearer in World War I, he carted the dead and wounded from the front lines. Like Edgar Mitchell, Teilhard had the ability to intuit a greater meaning from his immediate circumstances, to see out beyond the literal front lines to the outlines of a global consciousness.

Journaling during a brief furlough from his duties in war, Teilhard reflected on the paradoxical pressures that soldiers felt between the respite from fighting and the tension of being on the front lines.

Our future continues to be pretty vague, both as to when and what it will be. What the future imposes on our present existence is not exactly a feeling of depression; it’s rather a sort of seriousness, of detachment, of a broadening, too, of outlook. This feeling, of course, borders on a sort of sadness (the sadness that accompanies every fundamental change); but it leads also to a sort of higher joy. . . . I’d call it “Nostalgia for the Front.” The reasons, I believe, come down to this; the front cannot but attract us because it is, in one way, the extreme boundary between what one is already aware of, and what is still in process of formation. (Teilhard de Chardin 1965, 205)

What was being stirred up in Teilhard’s imagination was a profound shift of attention. The months on the front altered his perception. Decades later, he would acknowledge how the concentration of bodies, “the atmosphere of the front,” and the loss of boundaries between “natural” and “artificial” and between “physical” and “moral” inspired within him an epiphany. The human million, as he described it, had within itself a “psychic temperature” and an evolutionary throb. The isolated human being, like an unattached cell, was predisposed to join with others and become a more complex entity, “to coalesce into physical relationships and groupings that belong to a higher order.” Grounded in his scientific knowledge of biological evolution and now acting with a spiritual sixth sense, Teilhard’s capacity for observation was magnified. He described this as a “gift or faculty of perceiving without actually seeing, the reality and organicity [sic] of collective magnitudes . . . what emerged into my field of perception was literally a new universe” (King 1996, 60–61).

Decades before Edgar Mitchell gazed down from the sky and saw a singular planet, Teilhard looked up from the planet’s physical core and saw a web of psychic coherence, like a thin mist, rising above human consciousness. His mind had been rewired to see unity from multiplicity and diversity as elements that make up a larger whole. “Yes,” he wrote in The Phenomenon of Man, “from now on we envisage, beside and above individual realities, the collective realities that are not reducible to the component element” (Teilhard de Chardin 1959, 247).

Read More

by Alan Briskin | Empathy, Fields

A group of us were working on what was to become the Collective Wisdom Initiative, and we were staying by invitation at the Institute of Noetic Sciences’ new campus in Petaluma, California. They had not officially opened yet, and we were there during the same period that the Institute’s board of directors was also meeting — including its founder, Edgar Mitchell. This was in 2000, four years before Laszlo would publish his work on the Akashic field. In the evening, Mitchell wandered over to the dormitory where we were staying, curious about what we were up to. We in turn were interested in him and specifically how going to the moon influenced his decision to begin the Institute.

Without being overly dramatic, this experience had for me elements of mythic time, meaning that the chronological time we spent together had little relationship to the impact of our encounter. He told us how he had originally been slated to be part of the Apollo 13 mission, but events unfolded that changed those plans. Of course, the Apollo 13 lunar mission was aborted when an oxygen tank exploded during the flight and the crew had to return to Earth. In the wake of that near-disaster, Apollo 14 was a closely watched global event.

Read More

by Alan Briskin | Collective Wisdom, Fields, Online Courses

Looking back on my earlier collaboration to articulate collective wisdom, I believe we all shared a faith in the centrality of spirit, the evolutionary potential of the human species, and the reality of our interconnectedness. We believed ourselves inextricably bound up with each other, enfolded within the larger forces of nature and subtle energies largely invisible to conscious awareness. Collective referred to a larger concept of wholeness and wisdom to its role in addressing existential issues of life, grounded in principles of collaboration, nonviolence, and adaptability.

Deeply embedded in our work, but in retrospect not explicit enough, was a respect for the individual’s relationship to larger fields. In our initial Declaration of Intent, published in 2004, we began by stating:

We believe a field of collective consciousness exists — often seen and expressed through metaphor — that is real and influential, yet invisible. When we come into alignment with this field, there is a deeper understanding of our connection with others, with life, and with a source of collective wisdom.

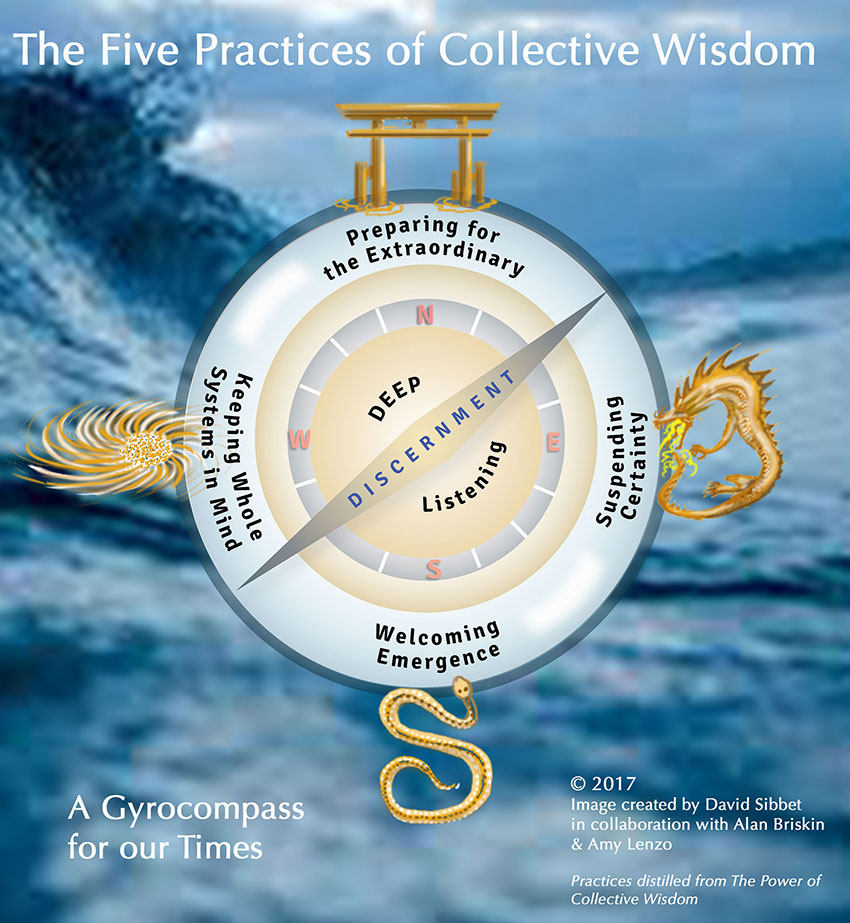

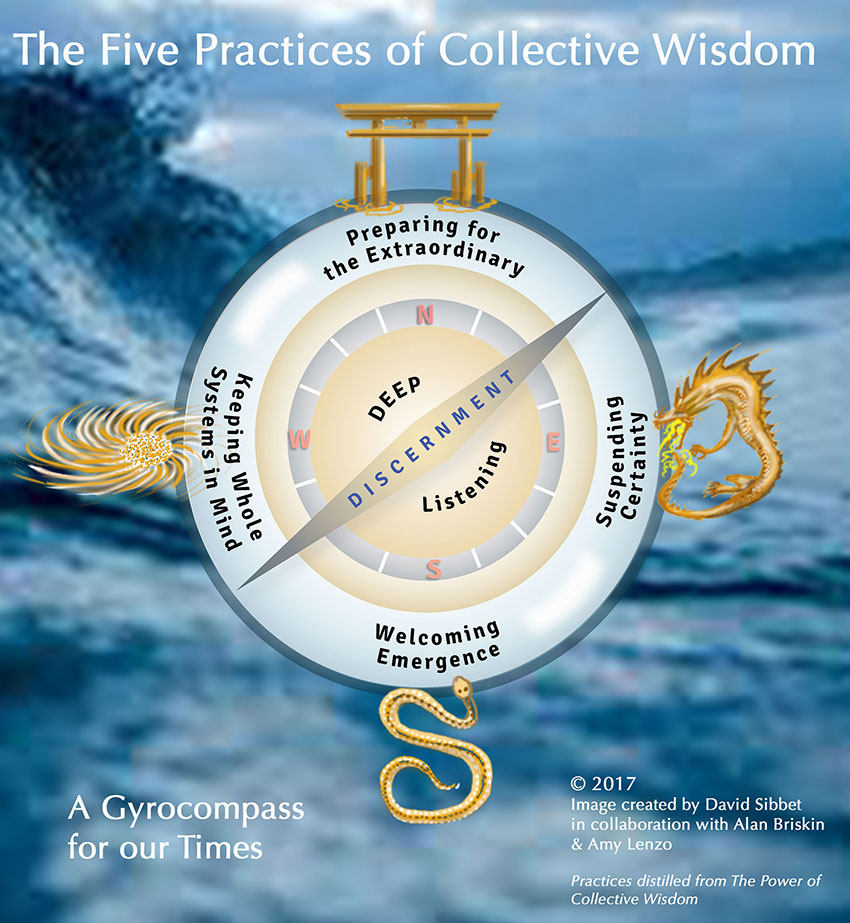

I’m now embarking on a six-session online program, Activating Collective Wisdom: Five Essential Practices, with Amy Lenzo, whose work with online environments and interactive group design makes her an excellent partner.

Early in our design process, she asked me about the relationship between the individual practices we are exploring in the course and activating collective wisdom in groups. In thinking about her inquiry, I am drawn back to the questions of fields. What different kinds of fields exist? What kinds of individual practices have the greatest impact on fields? How can we align, as individuals and as groups, with these deeper forces of connection? What is a path with wisdom?

I don’t have definitive answers to these questions, but they compel my attention and motivate me to inquire with fellow travelers. As the philosopher Jacob Needleman said with a mischievous smile, “I can’t tell you what wisdom is, but I know the wisest among us seek it.”

Read More

by Alan Briskin | Online Courses, Practices

This post was written collaboratively by Alan Briskin and Amy Lenzo.

When thinking something through it helps to think in images, as that can offer a unique approach to clarifying thoughts and seeing the relationship among ideas. It’s like translating between languages – conceptual ideas becoming representational, and images and symbols acting as a counterpart to abstract thought.

The reason for this lies in the very definition of image, literally an optical counterpart for an object. Similarly, imagination (from the Latin imaginari, meaning “to picture to oneself”) is an extension of this way of understanding. To the Romantic poets, for example, it was a way, through poetic expression , to picture something that was very real to them at the level of Soul, or Spirit. They weren’t making something up, as in our more common understanding of the word. They were making something visible that would otherwise be ephemeral but no less real. Images help us picture for ourselves ideas that can be elusive and difficult to capture in words alone.

We recently had a wonderful creative session with our colleague and visual maestro David Sibbet to create the above image (here’s a link to David’s description of our collaborative process). We wanted to represent practices of collective wisdom that we’ll be exploring in our upcoming six-session online course Activating Collective Wisdom: Five Essential Practices.

Read More