by Alan Briskin | Collective Wisdom, Consciousness, Health, Leadership, Poetry, Spirituality, Wellness

A poem based on phrases and fragments of a speech* given by Deepak Chopra:

My grandchildren are here today

the most important part for me.

Here is my question:

What if consciousness

was not

a byproduct of our brain?

What if instead

it is the ground of Being,

the basement of the Universe

in geometric space-time

where all co-exists

as possibilities.

The great Rishi wisdom teachings

tell us consciousness

cannot be imagined

but makes the imagination possible.

Can you imagine?

From the basement of space-time,

everything is born from a quantum vacuum,

Beauty, Truth, Love, Joy, Compassion,

and also our Diabolical Self.

There is only the collective mind

that shows up as the individual mind.

The sage plunges into it,

expresses it, becomes one with it.

Healing is nothing more than

the memory of wholeness

Nature can say that the

human species

was just an experiment

that didn’t work out

Or Not!

The frantic search for security

only reinforces the insecurity.

Surrender to the mystery

of the divine,

which is constantly on the move.

My grandchildren are

here today,

the most important part.

* Deepak Chopra’s speech, on which this poem was based, was given on the day he received the Goi Peace Award** in Tokyo, Japan, November 8th, 2010.

I was there as a moderator the following day for a panel discussion with Deepak and thought leaders from Japan on the subject of death and dying, and wrote the poem from fragments of his speech and the group conversation.

The mission of the Goi Peace Foundation, which sponsored both events, is to bring people together in wisdom, united in their hearts toward the common goal of peace on Earth. By encouraging public awareness and building cooperation among individuals and organizations in all fields, they aim to build an international peace network and stimulate the global trend toward a culture of peace.

by Alan Briskin | Books, Collective Folly, Conflict, Politics

In the late 70’s, I learned about the research of Nevitt Sanford. He was my professor and founder of the graduate school I attended. He was also one of the authors of a landmark research project begun shortly after World War II that resulted in the publication of The Authoritarian Personality . Catalyzed by the Jewish holocaust in Germany, they set out to discover if there was some pattern of human personality that allowed for the receptivity to prejudice that could lead to de-humanization and ultimately mass violence. He was one of the most gentle, thoughtful, and kind academic leaders I have ever known.

. Catalyzed by the Jewish holocaust in Germany, they set out to discover if there was some pattern of human personality that allowed for the receptivity to prejudice that could lead to de-humanization and ultimately mass violence. He was one of the most gentle, thoughtful, and kind academic leaders I have ever known.

The research, however, was quite controversial.

Illuminating at best, and suspicious science at worst (they used questionnaires to test for fascist tendencies and were heavily influenced by psychoanalytic language and Marxist concepts), the research nevertheless opened up my eyes to patterns of behavior that solved some perplexing questions I held. How could a person be simultaneously conventional in their social attitudes yet extreme in their viewpoints? Similarly, how could someone be both violently against what they perceived as control over themselves, yet seemingly willing to join others in denigrating and having power over others not in their perceived group? I was particularly struck by their description of what they called surface resentment. “We refer here,” they wrote more than sixty years ago “to people who accept stereotypes of prejudice from outside, as ready made formulae…in order to rationalize and – psychologically or actually – overcome overt difficulties of their own existence.”

Surface resentment is not the same as authoritarianism but it is a close enough cousin to be fanned by group passions. Weisberg in his column on the tea party writes that “nostalgia, resentment, and reality denial are all expressions of the same underlying anxiety about losing one’s place in the country, or of losing control of it to someone else.” In other words, a popular movement fanned by fears of economic, social, or status dislocation acts as a magnet on all surface resentments, especially for those who have felt ignored or pushed aside by multi culturalism, global movements in industry, and elites of various kinds who seem smug, arrogant, and disconnected from the difficulties of their own existence. This is why even if active tea party supporters are largely made up of older married white men of European ancestry with a Christian background; there is plenty of room for others who harbor resentment. The feelings are at once frustration that no one is listening to them and anger that there is far too much sympathy for gays, Muslims, blacks, Hispanics, and other out groups, far from the mainstream – or more insidiously replacing them as the mainstream.

Patrick Buchannan, the Republican candidate for President in 1992 and 1996 referred to this as “culture wars” and explicitly linked sympathy for these out groups with the nation’s decline. This week, the number one book on Amazon is The Roots of Obama’s Rage by Dinesh D’Souza, charging that Obama is driven by an anti-colonial ideology inherited from his African father and who seeks to diminish America’s strength, influence, and standard of living. And in a sad competitive clash of stereotypes among out groups exposed to discrimination, the CNN anchor Rick Sanchez was fired on Oct. 1 for disparaging the Jewish comedian Jon Stewart as a bigot. He argued that Stewart, like many middle class Jews and CNN staff, never faced real prejudices as he did having been born in Cuba and growing up in Florida – “I grew up not speaking English, dealing with real prejudice every day as a kid; watching my dad work in a factory, wash dishes, drive a truck, get spit on.” For Sanchez, the surface resentment against people not like himself burst forward as he denigrated Stewart for among other things, surrounding himself only with people like himself. We see in others the negative qualities that are so difficult to see in ourselves. And the ghosts of our original colonial identity as subject to power and the history of our maturing into a power that dictated to others is now coming back to haunt us in a myriad of twists and turns.

by Dinesh D’Souza, charging that Obama is driven by an anti-colonial ideology inherited from his African father and who seeks to diminish America’s strength, influence, and standard of living. And in a sad competitive clash of stereotypes among out groups exposed to discrimination, the CNN anchor Rick Sanchez was fired on Oct. 1 for disparaging the Jewish comedian Jon Stewart as a bigot. He argued that Stewart, like many middle class Jews and CNN staff, never faced real prejudices as he did having been born in Cuba and growing up in Florida – “I grew up not speaking English, dealing with real prejudice every day as a kid; watching my dad work in a factory, wash dishes, drive a truck, get spit on.” For Sanchez, the surface resentment against people not like himself burst forward as he denigrated Stewart for among other things, surrounding himself only with people like himself. We see in others the negative qualities that are so difficult to see in ourselves. And the ghosts of our original colonial identity as subject to power and the history of our maturing into a power that dictated to others is now coming back to haunt us in a myriad of twists and turns.

And it is not just the men. One female supporter of the tea party blogged that women are a critical part of the movement. “These are fierce women. These are women who have passels of grandchildren, who are heads of their families, respected decision-makers and rulers of their roosts… I think back to the report… on the Glen Beck event and the army of moms with huge garbage bags directing the hundreds of thousands to pick up after themselves. This is how we feel about America right now. We’re done waiting for you to clean up your trash. Momma sees a mess and darn it, you’re going to clean it up and you’re going to do it RIGHT NOW while we supervise. Now get over here and put that trash in this bag!” The metaphor is all about being in charge again, rulers of the roost, and about others who don’t pick up after themselves. Damn it, get in line.

I want to confess that on a personal level, I understand these various reactions to discomfort. When events seem out of control, I want to feel in control and it is at these times I am most inclined to react from surface resentments and project negative motives, even stereotypes, onto others – especially on those who differ with me.

At a group level, however, these dynamics describe elements of what my coauthors and I came to call collective folly. Collective folly is made up of two sides of the same coin. On one side is the movement toward separation and fragmentation. Group members resist ideas, other group members, or other groups that are deemed “not me” or “not us.” There is a tendency toward confirmation bias and the ignoring of divergent perspectives or data. At its extreme, destructive polarization is the outcome.

On the other side of the coin is the movement toward false agreement and the façade of unity. Group members appear to be unified, at least in what they are opposed to. The consequence is conformity within the group even if the ideology of the group supports individual rights, libertarian ideas, progressive politics and other ideologies seemingly contradictory to conformity. This movement masks a separation that already exists, among its members as well as outside itself, and consequently prevents the group from considering data and perspectives that could help it develop a more complete understanding of the reality it faces. At its extreme, unanticipated catastrophe can result.

What both sides of the coin have in common is a discomfort with complexity, paradox, ambiguity, and uncertainty. Both movements of collective folly ignore or explicitly distance themselves from divergent views and perspectives. The question is how do we confront these two movements of collective folly without being drawn into the very dynamics they describe.

Read the concluding essay in this five part series: What Can Be Done.

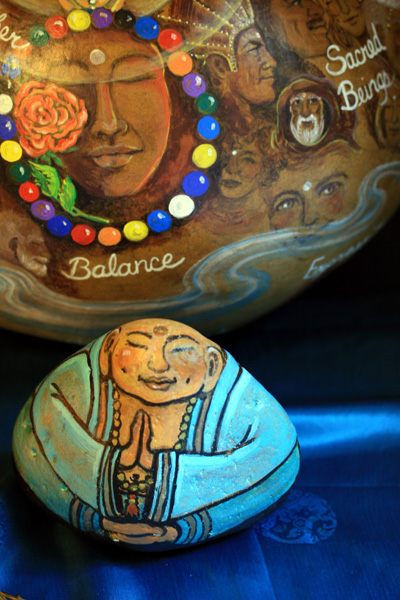

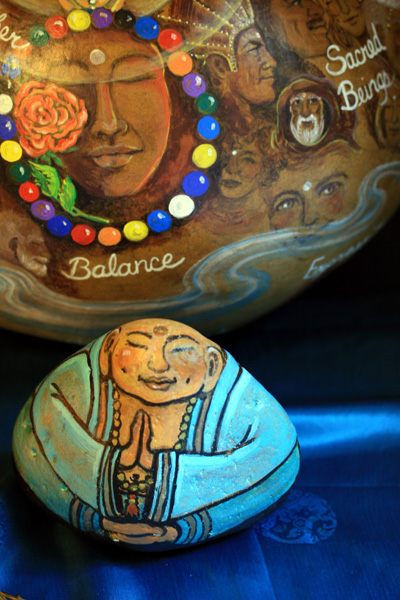

by Alan Briskin | Books, Photography, Quotable

Photo by Alan Briskin

Photo by Alan Briskin

"New capacity and intelligence emerges through connections: from cell to cell, dendrite to dendrite, human to human, group to group. As extraordinary and mysterious as the experience of profound connection—and of collective wisdom emerging—may feel in the moment, collective wisdom as a phenomenon is natural, even potentially ordinary."

~ The Power of Collective Wisdom: And the Trap of Collective Folly

by Alan Briskin | Conflict, Politics

“Rally Mohawks, bring out your axes!

Tell King George, we’ll pay no taxes…

On his foreign tea!”

~ Chant in the streets of Boston

on the night of the Boston tea party

Amid colorful signs and often in costume, the self identified tea baggers of today hold the celebratory energies of that revolutionary spirit. At a rally in New York City, Lou Dobbs, amid chants of “Throw the bums out” channels the same defiant zeal as those who once threw the tea overboard and marched in the streets of Boston. Exhorting the crowd to grasp their power in solidarity, he exclaims: “You are scaring the hell out of them.” He tells them “You, my friends, are dangerous—and I love that about you.” In translation, he is affirming that the ones in power (King George/Obama,) will not get our taxes for their foreign tea, be it a brew of tea leaves, health care reform or bank bail outs.

What distinguishes tea baggers from past right wing insurgencies, writes columnist Jacob Weisberg, is its “anarchist streak- its antagonism toward any authority, its belligerent self expression; and its lack of any coherent program or alternative to the policies it condemns.” Yes, and so it was with the 30 – 130 colonists who marched over to the docks thinly disguised as Mohawk Indians to cast out the tea; they too had no coherent program, they too showed their displeasure in belligerent self expression and they too had had enough of authority and rational discourse. In fact they came directly from a large gathering in which they learned that no resolution had been found for what to do about the disputed tea.

It’s not that supporters of the tea party do not have a coherent program but rather that they share a belief that the details can be worked out later.

One of the protesters at the New York rally notes he does not want to be considered scary, but rather someone who is here to fix things. He is 56 and has lived with chronic pain for 17 years from a fall while doing construction. From his perspective, he is barely getting by and blames the government in some way reminiscent of how the colonists must have felt at the hands of the British, powerless and frustrated. Resentment toward those that represent authority or power over them pervades the tea party movement. And this is where hauntology takes on added significance. Whenever there is a highly volatile mix of defiance and resentment, all the displaced ghosts of the past come rushing in.

Read Part IV of this five-part series: The Authoritarian Personality in Us All

by Alan Briskin | Conflict, Politics

Recently, I became acquainted with the concept of hauntology – a philosophy of history originating with the philosopher Jacques Derrida. It has been called the logic of ghosts because it upsets the easy progression of time as always moving forward in measured sequence and proposing instead that the present is simultaneously haunted by the past and the future. It is the logic of the specter, the shade, the blurring of distinctions among conventional categories that keep us safe but also isolated. Hauntology is the unsettling knowledge that our actions are neither cut off from history or immune to the forces of evolution.

From this perspective, the tea party takes on significance beyond its meaning in the moment.

All around this movement are shades of ghosts past and in particular the shade of those original Massachusetts colonists which gave the tea party its name. On December 16, 1773, dozens of colonists made a statement against British rule by destroying tea that bore a tax imposed by Britain (similar to duties it charged in Britain) but not authorized by local representatives. In New York and Philadelphia, the tea was sent back to Britain rather than pay duties and in Charleston, Virginia, the tea was left to rot because colonists refused to unload it. But in Boston, there was an outright revolt with a group of colonists throwing the tea overboard.

The spectacular show of resistance served to unite the various British political parties and in a display of solidarity they forced the closing of the Boston harbor and instituted a series of laws called the Coercive Acts, referred to by the colonists as the Intolerable Acts. And in turn, these coercive measures served to unite the colonists – for the most part. Samuel Adams argued the actions of the group who threw the tea overboard were a principled stand and not a lawless mob; Benjamin Franklin thought there should be reimbursement for the destroyed tea. At minimum, there was ambivalence among the colonists about the destruction of property, yet a seed of pride in their defiance. It took over a half a century for the seed to grow into what today we refer routinely to as the “Boston Tea Party” instead of simply “the destruction of the tea.” A party is far more celebratory than simply destroying things.

From most historical perspectives, the Boston tea party served to accelerate the political will to separate from Britain and led to the convening of the First Continental Congress which felt compelled to respond to the Coercive Acts. Britain, already reeling in debt because of its sustained military engagements, would now face a new insurgency and the eventual unraveling of its Empire. What was crystal clear at the time was that the “other” was in the wrong.

Read Part III of this five-part series: Serving the Ghosts of Defiance and Resentment